Mike taking some time to hunt.

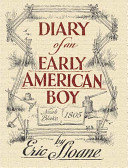

I recently finished reading Diary of an Early American Boy, and I was particularly impressed by how the seasons ordered the lives of Noah Blake and his family. As I discussed in my last post, the seasons can offer a rhythm for life, including a wholesome approach to work and the cues to rest. The Blakes’ agrarian context necessitated a variety of tasks and chores, and the changing seasons  with their specific conditions guided the family’s work and daily lives: seasons for sowing, planting, reaping, building, mending… They could not manipulate those conditions by will or whim.

with their specific conditions guided the family’s work and daily lives: seasons for sowing, planting, reaping, building, mending… They could not manipulate those conditions by will or whim.

With modern industry and technology, we are generally able to disregard this rhythm because we have access to manufactured versions of natural occurrences and the means to hasten or create convenience for natural processes; we have light bulbs and snow blowers and processed foods. Nevertheless, we have not entirely eradicated our dependence on the world around us. We still need clean water and healthy soil, the sun and wind and living beings around us. So we still have the opportunity to recognize something that industry and technology don’t make so self-evident.

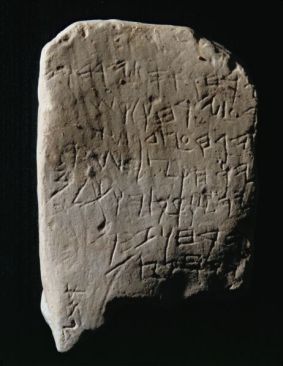

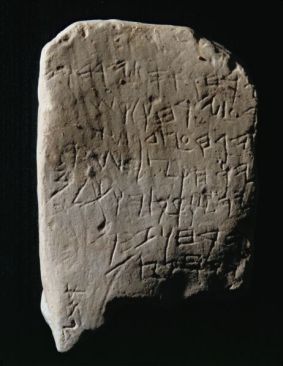

The Gezer Calendar (10th Century BCE West Semitic limestone tablet): Two months of harvest, two months of planting, two months of late planting, a month of hoeing flax, a month of barley harvest, a month of harvest and feasting, two months of (vine) pruning, a month of summer fruit. –From K.C. Hanson’s translation (www.kchanson.com). Photo Source: Center for Online Judaic Studies (www.cojs.org).

When we do things like grow the food we eat or build the homes we live in, they remind us that we are not masters of the world. We depend upon the longer days of sunlight in the summer and the seasons of rain and snow. We depend upon the toil and careful balance of the living beings around us, the bees and spiders and trees and seeds. We depend upon factors that are outside of our control and that spiral out of our control when we attempt to impose our version of mastery over them.

In the final months of my educational pilgrimage, I spent many hours steeping in Deuteronomy and Ecclesiastes and the early chapters of Genesis, mulling over the ways that these texts present the place of human beings in creation, as part of creation. With the ongoing discussions Michael and I have shared about our industrial-technological lives, these texts have resonated under and behind and within our own conversations.

I could expound on the specifics for any of these texts, but as this post is already becoming lengthy, I will focus on one. As I think about the rhythms of the world, I can’t escape the echoes of Ecclesiastes 3:

There is a time for everything,

and a season for every activity under the heavens:

a time to be born and a time to die,

a time to plant and a time to uproot,

a time to kill and a time to heal,

a time to tear down and a time to build,

a time to weep and a time to laugh,

a time to mourn and a time to dance,

a time to scatter stones and a time to gather them,

a time to embrace and a time to refrain from embracing,

a time to search and a time to give up,

a time to keep and a time to throw away,

a time to tear and a time to mend,

a time to be silent and a time to speak,

a time to love and a time to hate,

a time for war and a time for peace.

—Ecclesiastes 1-8 (NIV)

I first heard the poem as a child in the 80s from the movie Footloose (yes, the real Footloose), when Kevin Bacon (“Ren McCormack”) stands before the town council and urges, “Ecclesiastes assures us that there is a time for every purpose under heaven. A time to laugh… and a time to weep… A time to mourn… and there is a time to dance.”

In these past months, what has been provoking me about Ecclesiastes, and where I think it offers such an acute counter to the wisdom of our day (as with its own), is that it challenges our ambitions to triumph over the world. It undermines the assumption that we, human beings, can become masters of the world, or even masters of our own lives. (And if Ecclesiastes does have an intimate connection with Greek philosophy and thought, as many argue, there is a poignant critique of the Greek hero and the aspiration for immortalization through legacy. This critique resounds also to life in 21st century America, where the latter is pursued with no less zeal.)

It seems that we have found creative ways through industry and technology to attempt to remove ourselves from confrontation with our contingency. We rely on our buying power to secure food, medical care, resources. Yet when we face adversity or tragedy or unresolved injustice, we may recognize how tenuous our modern security is. We can say with Qoheleth, “And I saw that all toil and all achievement spring from one person’s envy of another,” or “I saw the tears of the oppressed—and they have no comforter; power was on the side of their oppressors—and they have no comforter,” or, “Surely the fate of human beings is like that of the animals; the same fate awaits them both: As one dies, so dies the other.” And with Qoheleth, we may declare, “Meaningless, meaningless…everything is meaningless!”

In a way, it seems to be an outlook that does little more than disconcert and dishearten. Yet maybe because we, Michael and myself, have spent so much of our time striving and coming up empty, we are finding this vision to be freeing. We are weary of choosing lives that are enslaved to the pursuit of security and acclaim. We are finding that words like those of Qoheleth ring true: “This is what I have seen to be good: it is fitting to eat and drink and find enjoyment in all the toil with which one toils under the sun the few days of the life God gives us; for this is our lot” (Ecclesiastes 5:18, RSV).

Through our observations and conversations, Michael and I are finding how little control we have over or in the world around us–but how great an opportunity we have to be part of creation and find enjoyment in it. With this recognition, we feel that we are also finding our place in the world and, ultimately, finding life.